Quotes:

Vyleta’s second novel is truly a work of art; his deft manipulation of narrative and characters (and readers), a master class in psychological sleight of hand. Although it’s early days yet, The Quiet Twin may well turn out to be one of the best — and most quietly disturbing — books of the year.

Sandra Kasturi for the The National Post.

Vyleta builds an atmosphere of fear and paranoia… With The Quiet Twin, he proves he’s no one-book wonder.

Margaret Cannon, The Globe and Mail

The novel pungently recreates the noxious ethos in which [Nazism] flourished, resembling Hitchcock’s Rear Window rescripted by Dostoevsky and Kafka.

John Dugdale, The Sunday Times

Vyleta … finds clever ways to subvert expectations. […] [A]s a result, the scenes of Beer’s increasingly dangerous attempts to protect his patient become utterly wrenching.

Andrew Haig Martin, The New York Times

Innocence and cunning, humour and pathos, sacrifice and cruelty — all operate side by side in a world gone wrong in this breathtaking page-turner.

Harriet Zaidman, The Winnipeg Free Press

Dark and disturbing, a novel of rare sophistication.

Bryce Christensen, Booklist (starred review)

Vital, deftly realised characters populate Vyleta’s simmering narrative. … The Quiet Twin is a sharp and confident novel that captures the social paranoia and mistrust fomented by Nazism. … Vyleta’s subtly engaging thriller is tense with violent acts.

James Urquhart, The Independent

Beer is both an anomaly and the norm: a perceptive mind subdued by sour principles; a compassionate heart in a cowardly body. When push comes to shove, as it nearly always does, what good are thoughts against brute force? …[N]imble, nuanced, fierce, scrupulous, [The Quiet Twin] makes a good case for the power of such thoughts.

Heather Thompson, The Times Literary Supplement

A compelling rumination on watching and watchfulness, served up with Nabokovian glee.

John O’Connell, The Guardian.

A striking, pitch-perfect, wonderfully atmospheric and beautifully written ensemble piece that subtly portrays a society on the brink of moral collapse. 5 Stars.

Toby Clements, The Sunday Telegraph.

Working primarily through mood, atmospherics, and the general air of malevolence with which he surrounds the action, Vyleta memorably conjures up the darkness both of the times and of the Nazi mind.

Lawrence Rungren, Library Journal

An evocative…portrait of life in a new police state.

Kirkus Reviews

“[A] captivating detective story…. readers will appreciate the novel’s well-crafted pathos, dark humor, and chills.”

Publishers Weekly

The Quiet Twin plays out the battle between the Nazis’ urge to eliminate society’s most vulnerable members and the humanist doctor’s duty to protect them. That the battle is unequal from the start does not detract from this tense, well-wrought novel.

Sam Sacks, Wall Street Journal

In two books, [Dan Vyleta] has shown that he can take milieux far removed from us—thrilling ones, horrifying

ones—and use them, with care and decency, to examine the limits of just what a human being can bear.

Stefan Beck, The Weekly Standard

[W]hile this work can be described as a mystery or thriller or story of suspense to those demanding the application of genre this implies that Vyleta is playing by the rules of the game. He doesn’t and that is his genius. … You will love this book.

Hubert O’Hearn, The Thunder Bay Chronicle-Journal

In 2008 Dan Vyleta published his astonishing novel, Pavel & I, set in Berlin in the immediate post-World War II years. [The Quiet Twin] is just as chillingly well observed

Alidë Kohlhaas, Lancette Arts Journal

[A] fully nuanced nightmare of reality. … The Quiet Twin is a searingly good book. … The temptation to reach for hyperbole is almost overwhelming.

Linda L Richards, January Magazine

Vyleta’s story of a crime in Vienna during the early days of World War Two makes him the heir to the throne left empty since the death of Graham Greene. Yes, he’s that damn good.

San Francisco Book Review

Full Reviews:

The National Post

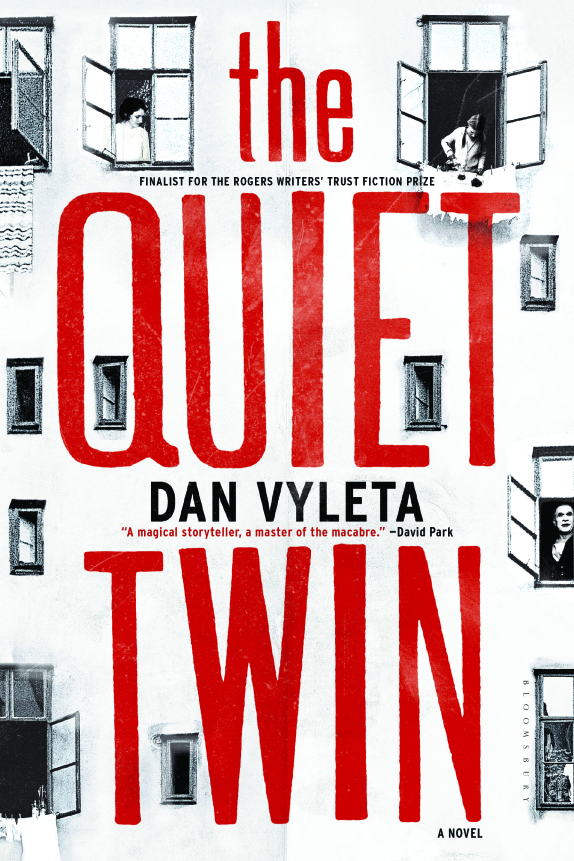

The Quiet Twin

By Dan Vyleta

HarperCollins Canada

288 pp; $29.99

Reviewed by Sandra Kasturi

Jan 28, 2011

A few years after the success of his first novel, Pavel & I, Dan Vyleta returns to 1940s Europe with another allegorical character study masquerading as a mystery-thriller. This time, he takes us to Vienna at the start of the Second World War, when the Nazis are just beginning to goosestep their way across the continent.

We are introduced to Dr. Anton Beer, a shy and reticent GP, and the other denizens of the apartment building he lives in: Professor Speckstein, the disgraced teacher and Nazi informant; his hypochondriacal and possibly over-sexed niece Zuzka, whose limbs go mysteriously numb on a regular basis; their sneering housekeeper, Frau Vesalius; the trumpet-playing Mr. Yuu upstairs; the hunchbacked girl Lieschen and her alcoholic father; Otto, the sinister mime; and, of course, Otto’s beautiful twin sister, Eva, who also suffers from an unknown paralysis. This cast of characters with their hidden faces and multiple secrets lends an even more claustrophobic air to the narrative, which is echoed by the very era the story is set in.

What makes Vyleta such an insidious writer is that the first part of The Quiet Twin seems like an atmospheric period thriller, as envisioned by Daphne du Maurier, crossed with some sort of police procedural: A Nazi cop ropes Dr. Beer into investigating a string of unsolved murders that have occurred in the vicinity. But then the true disquiet of the narrative starts to creep in, and with it comes the slow realization that this is a wholly different kind of book, and that nothing is as it first seems.

The cop demanding assistance from Dr. Beer initially masquerades as a patient who has come for a medical checkup — and then reveals his true identity, much to the doctor’s horror. But Dr. Beer isn’t exactly who he appears to be either; the cops want his help not because he’s a GP, but because he’s a psychiatrist who has read the forbidden works of Freud — a man who himself wrote much on the uncanny, and not surprisingly, on twins. In fact, the book sometimes feels like nothing so much as a trippy Freudian dream, or perhaps nightmare, in which nothing one sees (or reads) can be trusted, and where every character wears a secret, ominous face (sometimes literally).

Even Vyleta’s descriptions of objects or people in physical space — for example, how the characters are standing or moving — are often disorienting. It’s almost as if one can never be sure there isn’t an extra arm or leg there that doesn’t belong. Scenes of life as rendered by Escher, with Vyleta as the ultimate unreliable narrator. Or perhaps a commedia dell’arte play or pantomime; every scene a stage set with many doors, a more murderous version of Cabaret as directed by Fellini.

And that brings us to the crucial question, given the title of the book — who, after all, is the “quiet twin”? At first it seems obvious: Otto’s paralyzed sister Eva, who cannot speak, and whose outside beauty is marred by her rotting inside — surely a metaphor for Nazi Germany, with its inner corruption overlaid with the desire for Aryan perfection? But then we discover that Zuzka, too, is a twin, who writes letters to her dead sister. And there is Otto, Eva’s twin, the dissolute mime, who is literally silent during his performances, which themselves hold up a mirror to the soldiers who make up his audience — resulting in yet another kind of scenario full of doppelgängers. And then we have Dr. Beer, hiding his homosexuality from the Nazis and the rest of the world, as a kind of twin — sleeping not with his opposite, women, but men, his reflected image — and who keeps silent about many of the things he witnesses.

Lastly there is Lieschen — the little girl who is the moral centre of the story, whose voice is perhaps the only truthful one, more so even, perhaps, than the author’s — she, too, can be considered a mirror held up to the other characters and their paralysis, of limb and thought and emotion, echoing the paralysis of an entire

nation.

But The Quiet Twin obviously relates most powerfully and metaphorically to the rise of the Nazi regime and its horrors; as millions remained silent in the face of all that went on, mute, paralyzed, while their countrymen, those whose faces often looked just like their own, went on to commit atrocities on a scale that still seems almost incomprehensible; the Freudian manifestation of the other (terrible) self.

Vyleta’s second novel is truly a work of art; his deft manipulation of narrative and characters (and readers), a master class in psychological sleight of hand. Although it’s early days yet, The Quiet Twin may well turn out to be one of the best — and most quietly disturbing — books of the year.

http://arts.nationalpost.com/2011/01/28/book-review-the-quiet-twin-by-dan-vyleta/

The New York Times

THE QUIET TWIN

By Dan Vyleta.

Bloomsbury, paper, $16.

Andrew Haig Martin

Vyleta’s second novel is a riff on Hitchcock’s “Rear Window” set in the charged atmosphere of Vienna, 1939. When a pet dog is violently killed at an apartment complex, the subsequent voyeuristic sleuthing by the noble Dr. Beer, with the prompting and assistance of a strange young woman named Zuzka, reveals a mess of sinister activity taking place across the courtyard. Vyleta carefully lays out the elements of a traditional mystery — colorful, secretive neighbors as suspects, a corrupt police officer as a foil to the hero’s investigations — and finds clever ways to subvert expectations. Though he proves adept at deploying the requisite red herrings and other plot mechanics, Vyleta’s use of his historical setting emphasizes a broader point about the way Nazism perverted justice and decency on even the smallest scale. As an overenthusiastic Gestapo officer puts it, “I had been trying to dig up the truth, while what was called for was initiative. . . . Working towards the Führer. It’s the watchword of the age.” The book’s most gripping passages concern a mute, paralyzed woman who comes into Beer’s care. His observations of her, “the way her eyes moved, following the passage of the shadows as the sun inched forward through the hours of the day,” are the most tenderly written in the book. We are reminded, in one of a series of ominous interstitial notes, that the Nazis didn’t take kindly to those they considered “mentally or physically handicapped,” and as a result, the scenes of Beer’s increasingly dangerous attempts to protect his patient become utterly wrenching.

The Globe and Mail

MARGARET CANNON

THE QUIET TWIN

By Dan Vyleta, HarperCollins Canada, 284 pages, $29.99

Jan 20, 2011

Dan Vyleta’s auspicious debut novel, Pavel & I, was set in both the Old and New worlds, suitable for a man who’s lived in many places and now calls Canada home. The Quiet Twin returns Vyleta to Europe – to Vienna, Nazis and a serial killer. This is the world of small individual crimes set against a backdrop of pure evil. It is territory worked by major writers such as Philip Kerr, but Vyleta holds his own.

Dr. Anton Beer specializes in forensic psychology. He’s asked to investigate a series of murders in a Vienna apartment building. The man who asks is a Nazi, and Beer has more than one reason for wanting to be ignored by the occupying forces. When he takes on the care of a paralyzed woman, he has another reason to fear. Vyleta builds an atmosphere of fear and paranoia, but doesn’t lose the thread of his story. With The Quiet Twin, he proves he’s no one-book wonder.

The Winnipeg Free Press

Harriet Zaidman

February 5, 2010.

Riveting story ramped up by spectre of Nazis

THE foreigner, the loner, the imperfect — all are suspects in this gripping murder thriller, set in Vienna just after the German juggernaut has begun to roll across Europe.

Dan Vyleta, the author of Pavel and I, a post-Second World War spy intrigue, has written a riveting story with twists, turns and tension that is ramped up by the spectre of the growing Nazi terror.

It adds a frightening dimension to the lives of residents of a rundown apartment building, who learn about each other by watching through windows in the centre courtyard and peering through doorways in the stairwell. Curtains are drawn and doors slipped shut as neighbours hide secrets that could spell their doom under the New Order.

With delicate and ironic prose, Vyleta draws pictures of the dystopia that has become everyday, a presage of the brutality yet to come. Anton Beer, a young doctor, tiptoes through the broken furniture and shattered glass of a recently burned-out household. He “wondered for a moment what the neighbours made of this gutted building, then reminded himself that they were the same people who had witnessed (it) and done nothing. People like him.”

Events are complicated when Beer makes a startling discovery in one of the apartments. An emaciated woman, paralyzed and mute, stares out at him from a filthy bed.

Eva is pure, but her twin brother, a mime, is a summary of sin — a muscular, menacing lout whose his whiteface enables him to make crude political jabs at drunken Fascists. Yet he refuses to take Eva to the hospital. “I’ve heard stories,” he says of the Nazi treatment of the disabled.

Beer takes Eva in and tries to keep control over what goes on in his apartment. She is another secret to conceal. But there is no safety in a world where evil is a growing infection. Rumours become truth, paranoia prevails, chaos looms.

Vyleta’s characters make split-second decisions that test their humanity and decide their momentary survival. Strangers living in the same building are thrown into taking measures they would never have considered previously yet pretend that they are adjusting to the “new normal.”

They must trust each other while they expect betrayal and plan their next move. Vyleta describes their fear and stealth, their calculations and fated errors as they try to keep out of the hands of two different kinds of monsters. Beer’s investigation culminates in a surprising climax.

Vyleta grew up in Germany and now lives in Eastern Canada. A historian, he has also written Crime, Jews, and News, Vienna 1895-1914, which examines criminal cases and anti-Semitism at the turn of the last century.

He clearly understands the nature of the people and the tenor of the times. Innocence and cunning, humour and pathos, sacrifice and cruelty — all operate side by side in a world gone wrong in this believable, breathtaking page-turner.

The Independent

Something rotten in the state of Austria

Reviewed by James Urquhart

Sunday, 6 February 2011

Vienna, autumn 1939: Dr Anton Beer, a medic whose formal training embraces the deviant Jewish thinking of the banned Sigmund Freud, holds a general surgery in his apartment on the upper floor of a suburban tenement.

A needy patient in the same block is Zuzka, the niece of Professor Speckstein, who has been sent to the city to recover from an unspecified nervous condition. Beer considers her a hysteric, a sham, but dutiful house calls gradually draw him into the Speckstein household.

Disgraced after a rape trial but clinging to social power as a Nazi Party neighbourhood informer, Professor Speckstein coerces Beer into reviewing the evidence of a string of local murders – including the butchering of his own aged hound. Zuzka, audacious through boredom, on the cusp of womanhood (or in need of, as Speckstein’s housekeeper tartly observes, a husband), uses her despised uncle’s authority to pursue her own inquiries into the miserable fate of the family dog.

From her uncle’s apartment, at the affluent front of the block, Zuzka can peer into the windows of their neighbours in the two wings that overlook the shared courtyard, and what is observed serves as an ingenious driver to Dan Vyleta’s plot. The novel opens at a slow, wary pace that reflects the guarded private lives of the apartment block’s diverse inhabitants, all variously braced against the threat of notice by hostile authorities. But Zuzka’s reckless sorties into uncharted emotional territory, Beer’s reluctant probing, and an increasingly heavy police involvement steadily accelerate the pace of The Quiet Twin towards a denouement catalysed by a dinner party that Speckstein plans for the local Nazi top brass.

Vital, deftly realised characters populate Vyleta’s simmering narrative. Most pungent is Teuben, the boorish, unprincipled police detective whose swaggering, presumptive authority holds all the arbitrary menace of Austria’s eager pliancy to the Führer.

The gathering intensity of Vyleta’s tentacular plot allows the loosest of assonances with Hamlet. Zuzka’s seamy, mime-artist neighbour is roped into performing at the Professor’s ghastly soirée which, Zuzka vainly hopes, will expose her uncle’s guilty conscience. On an increasingly corpse-strewn stage, Beer dithers over his own courage and duty. More in tone than action, the malaise of the Nazi eugenics programme provides the rancid atmosphere of a rotten state.

Darker in tone than the ludic Pavel & I, Vyleta’s debut, The Quiet Twin is a sharp and confident novel that captures the social paranoia and mistrust fomented by Nazism. At the novel’s outset, startled by a doorbell, Dr Beer “jumped and feared arrest, irrationally” – an adverb that speaks of the timid doctor steadying his nerves with logic against the insidious but explicit criminalisation of the times.

Regardless of whodunit, Vyleta’s subtly engaging thriller is tense with violent acts that are, perhaps above all else, a manifestation of the era’s anxieties.

The Thunder Bay Journal Chronicle

Hubert O’Hearn

A full online version of Hubert O’Hearn’s review can be found at By The Books Reviews: http://bythebookreviews.blogspot.com/2011/02/quiet-twin.html

Lancette Arts Journal

May 2011

Reviewed by Alidë Kohlhaas

In 2008 Dan Vyleta published his astonishing novel, Pavel & I, set in Berlin in the immediate post-World War II years. He managed to create such a strong image of the city and its people that as a reader one felt he had to have been there during the dark days of 1945-7. But, of course, he was born a couple of decades later, which shows that a good writer can give us a true picture of a time long before his or her own time. In that way he reminds me of English writer Clare Clark who wrote about her hometown, London, in The Nature of Monsters and The Great Stink in the same intuitively understood nature of an era long gone by. Both writer understand how to form historical novels in a way that allow the reader to feel they have actually moved into a time long gone, but still very much alive.

Now Vyleta has released yet another novel, this time set in 1939 Vienna. It is just as chillingly well observed as his first novel, although it is more muted—or at least when it starts—than the Berlin story. Titled The Quiet Twin, is set in a block of apartments peculiar to continental Europe prior to WWII in which buildings are set around a central space. Berlin, for instance, was famous for its Hinterhöfe (rear courtyard), and most likely they were called that in Vienna as well. The idea was that those who were able to afford apartments with windows facing the street were of means and of “station” in life; the residents, whose windows faced the central courtyard, were of a lower station in society: the workers and even the dispossessed. It created a peculiar social mix that in a class-conscious European society merely emphasized the disparity between the haves and have-nots.

Vyleta’s novel transports us into the tense atmosphere of 1939-Vienna, a year after the Anschluss (annexation). In this new world many people kept their heads down, their ears covered and their eyes shut. In that way they were not unlike many others in countries where the Nazis had become the master, including Germany. By turning inward, the population became an unwitting collaborator with the Nazis. If we did not already know this then Vyleta’s tale makes it abundantly clear. Of course, there were also plenty of Austrians who welcomed the arrival or the election of the National Socialists, and who used their newly acquired positions to their advantage. This is, after all, not the world of Julie Andrews and the von Trapps. In the particular Viennese tenement where Vyleta has set his story, most tenants keep their heads down for reasons that slowly unfold as the tale progresses.

The Quiet Twin might be described as a historic mystery thriller, but I am loathe to classify Vyleta’s book in this manner. There is something deeper going on. Both his novels are social and psychological studies without being so in an obvious manner. In Pavel & I the author explored the survival instinct after the breakdown of a city’s social fabric following war, mixed with the intrigue of spies and the mounting tensions between former allies in a struggle to dominate Berlin. Some may point to Graham Greene here, but that writer actually experienced the world he wrote about. In The Quiet Twin a different kind of breakdown of the social fabric has occurred. Vienna is a place of rumors where dangers are whispered but remain unconfirmed. We, on hindsight, know that those rumors were either already true or eventually became reality, but the characters in this book are left to surmise about truth and lie.

To set the tone for his novel, Vyleta divided it into parts and sections with separate chapters. Part I is called Killers and before he starts the actual novel, he offers up a page about one of Germany’s serial killers from the first half of the 20thcentury. Readers, who think serial killers are peculiar to North America, will be enlightened here to an unfamiliar face of the supposedly orderly German world. Beneath the order lies a darker world in which serial killers are quite numerous prior to the ascent of the Nazis and even during the regime’s early years. The biggest serial killer, of course, was the Austrian/German, Adolf Hitler, who directed others to do the killing for him, but the author leaves it to us to make that connection.

Part II is titled Marvels, Part III Cretins, and Part IV is called Whispers, Echoes. Each part and each section within these parts is fronted by one of these curious pieces of information about strange personalities or occurrences that have played a role in the formation of the German and Austrian psyche during the last century, and which still has an impact on the present.

The novel opens with an introduction to young Dr. Beer, who appears to be going out on a date, but one that never materializes. Instead he is called to see a young patient in his own building. She is Zuzka, the niece of the Zellenwarten (not dissimilar to the Communist Chinese “granny” block wardens), whose job it is to spy on his fellow tenants for the Nazis. A disgraced professor, Dr. Speckstein has regained some social standing through this minor role in the Party. Zuzka, it seems, suffers from strange afflictions that upset Speckstein’s housekeeper, Frau Vesalius. It is through the young woman that Dr. Beer becomes aware of his fellow tenants who live in the less desirable apartments across the courtyard.

Zuzka, obviously bored with her existence in her uncle’s apartment, has spent much time observing what goes on across that courtyard. She points out to Dr. Beer the collection of unusual characters who inhabit a very different world than theirs. Among them are a mime, who appears to be hiding someone; a Japanese trumpeter, who lives in a tiny attic; a little hunchbacked girl, Lieschen, who plays a fairly pivotal role in this book; her father, who is an alcoholic and whose wife abandoned him and the child; and the complex’s janitor, who conducts a strange business in the basement of the building. Add to that mix the uncouth Detective Teuben, who seeks out Dr. Beer for help in forming a psychological profile of a killer. This boorish Nazi detective implies that one of the victims of this killer is Prof. Speckstein’s ancient dog. Since profiling, using method formed through psychoanalysis, was forbidden under the Nazis, Teuben’s unusual request adds an extra nuance to this novel.

As the reader meets each of these characters, and as they take on their distinct personalities, the novel begins to accelerate in pace, action and paranoia. The connections between these individuals become clearer and clearer as their fates intertwine, not always for the better. There are no happy endings in this book. There simply cannot be considering what was to come as the year 1939 turned into 1940 and lives under the Nazis took on an increasing macabre tone. It is to Vyleta’s credit that he not only engages readers, but makes us care about what happens, and at the same time makes us aware how quickly a seemingly highly developed society can sink into chaos and dysfunction.

Booklist

Starred Review

Dec 2011

by Bryce Christensen

When the police show up to investigate the corpse in an apartment courtyard, they immediately tug on his hair to make sure it is not a wig. In the endlessly deceptive world Vyleta unfolds, such skepticism about appearances is essential. And no one needs such skepticism more than Herr Doktor Anton Beer, the novel’s protagonist. Accustomed to dealing with the hidden illnesses lurking in the seemingly healthy and the feigned sicknesses of malingerers, this cagy physician unexpectedly finds himself prying for clues revealing who has recently butchered a local professor’s dog and, perhaps with the same knife, also murdered four humans.Through Beer’s sharp eyes, readers peer through peepholes, stare through parted curtains, catch fugitive images in mirrors, and scan stairwells, all the while assessing the inscrutable features of the residents of a Viennese apartment complex in 1939: a paralyzed woman shrouded in mysterious secrecy; her twin, a stealthy mime; a bookish Japanese trumpet player; a reclusive widow; an attractive hypochondriac; a drunken janitor. As Vyleta weaves his taut narrative, readers strive with Beer for that acuteness of vision necessary to anticipate and explain the ominous twists of events played out in the shadow of Nazi fanaticism. Dark and disturbing, a novel of rare sophistication.

The Weekly Standard

by Stefan Beck

May 28, 2012

Viennese Waltz

The second novel from a master of historic horror.

Graham Greene famously divided his books into two categories: novels, and what he called “entertainments.” He wished from time to time to indulge an appetite for pulp, and it was only fair to let his readers know what they were getting into. The joke, of course, is that, being Graham Greene, he never wrote anything even close to pulp fiction. Nobody could possibly mistake Greene’s antic satire Our Man in Havana, which he subtitled “An Entertainment,” for, say, the adventures of Blackford Oakes.

The novelist Dan Vyleta, who owes a significant debt to Greene, would run into the same problem if he set out to write an embossed-jacket potboiler. The raw materials are certainly all there: Vyleta, the German-born son of Czech refugees, holds a doctorate in history from Cambridge, and his work draws on a wealth of historical knowledge. His debut, Pavel & I (2008), is a spy novel set in Berlin during the brutal, brutalizing winter of 1946–47. His new book, The Quiet Twin, is a police procedural boasting Nazis, serial murder, and dark, shameful secrets. There’s even a rather unsavory mime, for good measure.

Unfortunately for Vyleta, but fortunately for us, he just isn’t a bad enough writer to ride this stuff to the bestseller list. It’s possible to read Pavel & I almost to the end without quite registering that it’s genre fiction. Espionage and violence are incidental to a more probing story about how human psyches bend or break beneath hardship. The central mystery is less fascinating than the Dickensian grotesques: Pavel, a decommissioned GI with kidney problems; Anders, the boy spiv who becomes his caretaker; Sonia, their upstairs neighbor, mistress of villainous Colonel Fosko; and Peterson, the unlikely narrator, a one-eyed operative who, tasked with torturing Pavel, instead falls under the spell of his quiet intensity.

Much of Pavel & I takes place in a tenement building, and almost all of The Quiet Twin does. The setting works to a different effect in each book. In Pavel, it creates an uncomfortable sense of waiting, marking time, hiding out—dull dread. In The Quiet Twin, the building is not in postwar Berlin, but rather Vienna in 1939. It will come as no surprise, then, that The Quiet Twin is about surveillance, paranoia, and the mounting fear that one doesn’t know nearly enough about the people with whom one is surrounded.

It is a fascist state in miniature, a nightmarish dollhouse in which everyone can look into every room. That isn’t to suggest that the tenants of Vyleta’s building are symbolic, or that their intersecting stories are in some way allegorical. They are real (if anything but ordinary) people whose lives have been disrupted, set on edge, both by the rise of the Nazi party and by a string of local killings. The most recent is the disembowelment of a dog belonging to one Professor Speckstein, a disgraced doctor turned Nazi Zellenwart, or neighborhood supervisor and informant.

The hero, so to speak, of The Quiet Twin is another doctor, 34-year-old Anton Beer, who operates a small practice out of his apartment and is treating Speckstein’s niece Zuzka for an apparently hysterical illness. One night, Speckstein summons Beer, gives him confidential files on the murders (“I have some influence, you understand”), and explains, “Somebody killed my dog. I have reason to believe they may be after me.” It turns out that Beer is not only a doctor but also a scholar of forensic psychiatry— not a great thing to be at a time when familiarity with Freud could invite unwanted scrutiny.

Soon everyone is an amateur investigator, and everyone is, as they say, a suspect. Zuzka reveals, a little too casually, her own penchant for voyeurism, showing Beer how her window looks out on the courtyard and into other apartments. In one lives 9-year-old Anneliese Grotter and her alcoholic father; in another, a mime:

[H]is face emerged, greasepainted, out of the darkness of the window: hung wide-eyed, unmoving, at the very centre of its frame, held up by neither noose nor neck nor block of wood. When [Zuzka] had first seen him, disembodied it had frightened her and made her take him for a ghost. Then he had stripped one night, had peeled off sweater, gloves and tights, and hung them out into the wind, so very black that they cut deep holes into the fabric of the night. . . . [I]t was tempting to think of him as nothing but a face: paper white, with hairline cracks running through its cheeks where the paint had dried and flaked upon his skin.

Much of Vyleta’s description is written in a kind of morose, monochromatic poetry, and it would not be mere blurb-speak to say that it can be haunting. In this, as in many other scenes, we are reminded that not all watching is malicious or invasive; much of it is done in loneliness and desperation, boredom and curiosity. It is, nevertheless, curiosity that will get Zuzka into trouble: She learns that the mime keeps a woman confined to his apartment, and she sets out, like the heroine of a children’s book, to find out what’s afoot.

Though character is a greater asset to Vyleta than plot, he does craft a pretty topnotch story, and it wouldn’t be right to give too much of it away. It is enough to disclose the following: The stoic, tight-lipped Beer, whose wife has left him for obscure reasons, is hiding at least one fact about himself. Zuzka, who tempts fate by confronting the mime, escapes not wholly unscathed: Against the reader’s too-logical expectations, she falls for him. Anneliese Grotter endures something so shattering that the reader will be forgiven for wishing Vyleta would let just one ray of sunshine into his benighted city block.

The Quiet Twin (like Pavel & I) features a villain it would be too charitable to call larger-than-life: Teuben, the corrupt Nazi police inspector (was there another kind?) who engages Beer in a campaign of infuriating harassment and blackmail. In a book flyblown with misery, sickness, and existential horror—Graham Greene would be proud—one little domestic scene is almost too much to bear:

A child came into the room, nine years old, his hair jet black like his father’s. He had a milky and somewhat sickly complexion and was prone to coughs. Quickly, with light, rapid steps, he walked up to the seated man, pressed his face into the sleeve of his uniform, then began to clamber into his lap. Teuben was indulgent with his only living child and helped him to gain his perch. . . .“What are you reading, Daddy?” Robert asked, scanning the newspaper articles and the pages of notes Teuben had assembled on his desk.

“I am reading about a girl only a few years older than you.”

Teuben’s intentions toward the girl in question are far from pure. It seems that evil, wearing the greasepaint of banality, isn’t really so banal after all.

The mime, Otto, turns out to be the player whose motives are easiest to pick out in this goulash of neurosis, fear, and evil. He is also the centerpiece of some of the most beautiful, balletic passages of action and description in either of Vyleta’s books. One does not expect to read about a mime without being irritated. (Then again, Vyleta incorporated into Pavel & I those two great mainstays of hack comedy, the midget and the monkey, without straying an inch from high seriousness.) Two scenes, one in which Otto performs for soldiers departing to the front, the other in which he’s the entertainment at a dinner party of Nazi officials, are too long to quote and too good not to withhold. They must be read in context.

“I think my resistance to the Nazi era,” Vyleta said in an interview, “was partially there’s a lot of clichés these days around it. . . . I didn’t want to write something that felt exploitative of the period. In particular, there’s an element to the plot, the whodunit part, and even the serial murder part, that could easily become very schlocky.” So Vyleta wrestled not with the impulse to call The Quiet Twin an “entertainment,” but with the earnest fear that someone else might. There’s no danger of that.

In two books, he has shown that he can take milieux far removed from us—thrilling ones, horrifying ones—and use them, with care and decency, to examine the limits of just what a human being can bear. Never mind his improbable twists, his lurid tableaux, his Nazi evildoers. With apologies to The Third Man and Harry Lime, Vyleta isn’t interested in cuckoo clocks. Neither is literature.