dan vyleta: writer

dan vyleta : writer

Get ready for crow season! Shortlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize "There was something wrong with his eye, the one that faced the window and found its own reflection in the darkness of the pane. It looked as though it had been beaten, broken, reassembled. Its...

International Literacy Day

Have a look at this depressing info graphic by GRAMMARLY about global literacy levels. Reading is a form of power. Let’s help people to empower themselves.

https://www.grammarly.com/plagiarism-checker

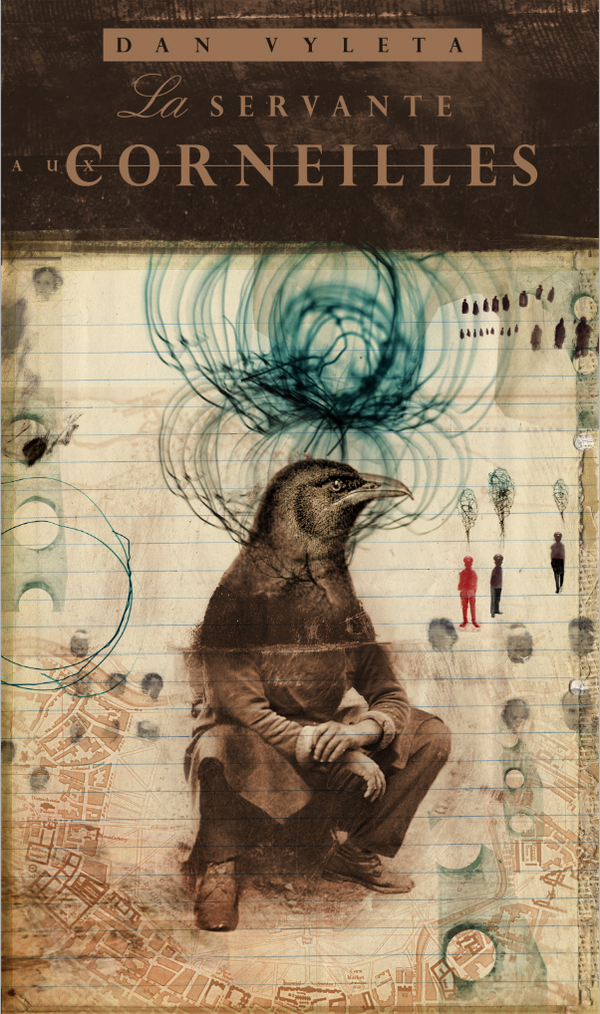

Crow Servant

Great title. Great cover. Out in Quebec. Thank you Alto!

Windows to the Night

Alto has revealed their cover for the Quebecois edition of THE QUIET TWIN. And readers have a chance to win free copies. How kick-ass is this?

Words Without Borders

A celebration of Czech writing in the November edition of Words Without Borders — nice to see!

Wicked Crooked

The UK paperback cover for Crooked Maid has been unveiled. Hot stuff! I love the red scarf…

Ghostwritten Selves

June 2014

I received an email the other day, advertising a service that writes blog entries for authors and artists. It came with a suggested title for the first entry (“The Journey of Writing” or something of the kind). Now I have often been told that we are in the age of the writer-as-entrepreneur in which social media presence is regarded as part of one’s “capital”, a way of building one’s “brand”. Still, I was a little shocked. We are living in a world where we market our (virtual-but-real) selves, responding, I suppose, to a hunger for connection, across globalised space. It is clear that the selves we put out there on our Facebook and Twitter accounts are not quite the same thing as the real me or you; social media provide a highly controlled/controllable window to our souls and most people draw the curtains over select parts of their lives, for entirely honourable reasons. But the thought that having a regularly updated public persona is so important to a writer’s economic well-being that he or she outsources the representation of their selves to a business that will speak for them (appropriately, with a humorous touch, tailor-made to their respective website needs) is frightening to me. Frightening and a little wrong. I understand, of course, that authenticity is an elusive concept: the more we crave it, in ourselves and in others, the more we become aware of the complex, swirling fog of our lives that is given contours only through story and performance. But to altogether abandon the dream of meeting each other eye-to-eye — “simply”, “unaffectedly”, as Dostoevsky puts it — and to start feeding my readers some market-tested version of myself (i.e. a lie): it really sends chills down my spine.

I know you are asking yourselves right now whether this is the real “I” writing. Let us hope it is.

Crooked Lines

February 2014

BBC Radio 4’s ‘The Saturday Review’ discussed The Crooked Maid last night (and did so very kindly — it cost me some nerve to listen, and then I was blushing and kept having to leave the room). [http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03sr0x8]

Egon Schiele came up, for his sense of line — crooked lines for my crooked maid, you see. I love Schiele’s work, have spent hours staring at his paintings and drawings in Vienna’s Leopold Museum and once upon a time copied some of his arms, some wrists and knotty fingers, into a sketchbook, trying to decipher Schiele’s magic. And yet I never thought of him when writing Maid (though, from now on, I doubt I will ever not think about Schiele when I open the book). It’s fascinating to me that someone can articulate a truth about my book of which I was unaware. It reassures me because it means I do not control what I create; that the book is richer than my sense of it.

Reading

Jan 31, 2014

Lovely reading in Bath yesterday, at Topping & Co. We don’t get to do this enough, us writers, meet our readers, look in their faces, hear them react to our book’s rhythm, to its jokes, to a harsh word spoken by a character. And what a magical kingdom of a bookstore! The kind where you want to sit down on the floor, pull books off the shelf and pile them up high all around you, browse for hours at a time (I’m not sure Topping would actually appreciate this strategy… but still!).

Launch day (and a bottle)

Jan 17, 2014

Launch day in the UK. And here I thought the book wasn’t out until the 30th ! I learned about it in the nicest possible way: an email from my editor, followed by a bottle of fine vodka arriving at my front door. A card tells me that the vodka honours Karel Neumann, The Crooked Maid‘s inveterate drunkard who is my homage to The Good Solder Svejk (another sly Czech with a taste for drink). May they break bread together in some literary great beyond (“after the war, at The Chalice, at six” as Jaroslav Hasek has it).

First UK reading: Topping & Company, Bath SPA, Jan 30, 8 PM. Call it a launch party. I might even take my vodka along. Hope to see you there!

Made the List Again

17 Nov, 2013

This came out last week.

Amazon.ca has announced their Best Books of 2013!

The Top 100 Editors’ Picks include:

The Empty Room by Lauren B. Davis

TransAtlantic by Colum McCann

Going Home Again by Dennis Bock

The Crooked Maid by Dan Vyleta

Drink by Ann Dowsett Johnston

Nocturne by Helen Humphreys

The Massey Murder by Charlotte Gray

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion

The English Girl by Daniel Silva

Now I hope everyone goes out and buys all of them in their local, independent bookstore. 🙂

Eleven days since the gala…

16 Nov, 2013

…and I am still picking through photos. What a fun, great, generous bash it was! Thank you again, dear Gillerites and Gillerettes, you all rock! And here a picture that’s been making the Twitter rounds. The CBC guy said “Jump”. So I jumped.

New Frock, Same Old Crooked Maid…

1 Nov 2013

…but looking mighty fine. The new Canadian “trade” paperback edition. With lovely cut pages and a very tactile cover. I signed 400 crisp new copies just yesterday… 🙂

Fanboy

Oct 16, 2013

I look at this collage of past Giller winners and get weak knees. What a group of writers. And it looks like I’ll get to meet some of them! Is it done to ask for autographs?

Shortlist

Oct 11, 2013

I still can’t really believe it. And Alice Munro won the Nobel! A week full of amazing news. Congratulations to my co-nominees. And to Alice who is making us proud to be writers.

I still can’t really believe it. And Alice Munro won the Nobel! A week full of amazing news. Congratulations to my co-nominees. And to Alice who is making us proud to be writers.

Go Canada!

I am going to order a T-shirt that reads: ‘Esi Edugyan, Margaret Atwood and Jonathan Lethem read my book’

Oct 16, 2013

Of the [Scotiabank Giller Prize] longlist, the jury writes:

“These are essential stories. Each of these novels and story collections offer a glimpse of who we are, who we might be. Whether set in postwar Vienna, or 1970s Montreal, contemporary Afghanistan or Newfoundland, each of these books took us out of ourselves to places that were at times uncomfortable, at times exhilarating. Some of the short stories in these collections exhibit a scope and breadth one would normally associate with a novel; some of the novels on this list have the distilled intensity one expects from short fiction. But all of these books surprised us with their formal rigour, the ferocity of their vision, and their willingness to tell unknown stories in remarkably familiar ways. These thirteen books remind us, once again, of that particular beauty only the written word can realize. This is writing at its finest.”

Yesterday would have been my dad’s 70th birthday. I wish I could call him today.

Canadian Bestseller (Eat Your Heart out Frederick Forsyth)

August 29, 2013

Well, you know what I mean…

MacLean’s Sept 9 edition Fiction Bestseller List is just out. As every writer knows — it’s great to be read. Thank you!

Why I think you should buy both the e-book and the hardcover!

Two weeks to go, and The Crooked Maid is out. In Canada and the US, that is: UK readers will have to wait till January. This week, my first two copies of the US (Bloomsbury) edition have reached me and remind me that books — other than being stuffed with words, stories, and paper-people to love and hate — are also objects, and as such can be beautiful. And as I sit stroking the undulating line of The Crooked Maid‘s cut pages (go ahead, picture it!), I must confess that, while e-books do have their moments (such as downloading the complete Chekhov in a manner of seconds, for next to no money, and knowing for certain one will never again be stuck at an airport with nothing to read), there is something very nice about holding the real thing, and leafing through its pages.

And as I write this, my editor at Harper Canada sends me this image of their own edition, along with a note that my copies are on the way.

Sweet.

Bone Winter, Paperweight

Here is the cover of the forthcoming German paperback edition of Pavel & I, rechristened Knochenwinter (Bone Winter), and coming to your shelf in the cunning guise of a crime novel.

Nice, moody image, no?

Full Paper Jacket

April 17, 2013

Sure looks pretty!

Chinese Travels

February 17, 2013

To read is to travel: both activities open new perspectives on the world. Sometimes this is more literally true than at other times. I have of late embarked on a literary journey through China that started with a Mo Yan short story in the New Yorker (‘Bull’), which led me to his Garlic Ballads, which in turn gave rise to a conversation with a Chinese visitor who put me on to Yu Hua (China in Ten Words; Chronicle of a Blood Merchant) who in turn got me hooked on Lu Xun (or Lu Hsün, or even Lu Sin, as he signed himself in Latin script, against all rules of romanization).

Yu Hua’s account in China in Ten Words of the meaning of literature, of the acts of reading and writing, during the years of the Cultural Revolution are humbling for anyone who has grown up in easy reach of books, but it is his endorsement of Lu Xun’s writings for which I am particularly grateful, for it has led me to discover an author whose works I would have been unlikely to stumble on in a bookstore or even a library (the most recent edition I found dates from the 1970s; most of the translations were done in the 1930s). Nor can it have been easy for Yu Hua to make his endorsement, for Lu Xun turns out to have been the one author of prose fiction who was shoved down the nation’s collective throat in the 1960s and ’70s when works of fiction had disappeared from libraries and private collections, and tatty copies of Dumas were traded furtively by schoolboys, like pornography or drugs. Along with Mao, Lu Xun (though already long dead and buried) became the voice of the party, which is to say of truth: endlessly cited, his fiction was held to unambiguously demonstrate the moral superiority of Chinese-style communism.

This fact is confounding, because – from the half dozen or so stories I have read thus far – he strikes me as a writer with a deep, Chekhovian distrust of anything that could be construed as a moral. From the point of view of his stories it does not come as a surprise to read the following comments which he made to the propaganda cadres at Whampoa Military Academy in 1927. With regard to the use Lu Xun/Hsun/Sin was put to by the Maoist regime, however, they are nothing short of astonishing:

Writers at this revolutionary center are probably inclined to emphasize that there is a close bond between literature and revolution, that literature should be used to propagandize, to advance, to incite, to help carry out the Revolution. But I think this kind of writing will be without effect because good writing has never been produced under orders from other people; good writing is free, an expression of the natural outpouring of the heart. If you first hold a thesis and then try to illustrate it accordingly, your writing will be just like an eight-legged essay. It will have literary merit, but no effect on the readers. So, for the revolution’s sake, let’s have more workers for the revolution and not be in a hurry for “revolutionary literature.” (as quoted in Harold R. Isaac (ed.), Straw Sandals (MIT Press 1974), p. xxiii).

A friend and aspiring writer recently told me that a writing teacher at a well-known Canadian institution disparaged her reading of foreign, passé authors on the grounds that writing has moved on, and recommended that, in her search for inspiration, she focus on successful contemporaries closer to home. I find this advice baffling, and against the spirit of literature. For reading, too, “is free, an expression of the natural outpouring of the heart”. Nor do I think that artistic inspiration – and for that matter literary technique – are best acquired by limiting one’s horizons, culturally, stylistically, temporally. That strategy, too, may result in writing that reads like an “eight-legged essay” in Lu Xun’s wonderful phrase. I, for my part, have never regretted a journey, whether it was conducted in person or by opening the covers of a book, and have been grateful, these past weeks, for the opportunity granted to me by a host of translators, to roam where I have not yet had the opportunity to set a single one of my eight feet.

Line Edits

December 29, 2012.

I am knee-deep in line edits. “Line edits” are that part of the editorial process when all the conceptual, big-picture work on the manuscript has been done and it is time to get down to the nitty-gritty, and scrutinize the language itself. It is the moment when adjectives get queried, and sentence lengths; where every violation of good taste, good style is flagged. We talk about pace, whether a sentence or paragraph will read a beat faster if we remove a word or sub-clause, and we hunt down unintentional repetitions. It is the stage in the editorial process when a writer stands confronted with his or her own ticks, their overused phrases, that word they have been misusing for years. It isn’t the last stage of the process, because the copy edit is yet to come – which has even stricter standards of correct usage, and much less interest in artistic license – but in many ways it feels like the last real chance to improve the book, make it all it can be.

Embarking on it, I was nervous. I had stayed away from the manuscript for several months in an attempt to give myself “fresh eyes”. There was no telling how it would seem to me now, returning to it. There is always the fear that the work will fall apart after yet another reading, that the sentences will seem strange and have lost their power to move me.

Thankfully, this has not been the case. From the first sentence and paragraph, a sense of recognition set in, not just of the characters and scenes, but of the sensibility evident in every word choice and every clause. In fact, the immediacy of the recognition was a shock. It isn’t just a matter of being reassured by the fact that I still like the book. The startling fact is that I can pick out minor editorial interventions – the cutting of a comma, of an “and”, a rearrangement of a sentence so that it starts off with “Three days later…” rather than finishing with the phrase – from a text that, in manuscript, is nearly 500 pages long, and do so at once, unthinkingly, without the slightest hesitation. Interestingly, this sensitivity to change does not seem to be primarily a function of memory. I do not actually remember the comma, or the missing “and”. Rather, what registers is the alien rhythm of the sentence, the sense that someone else’s aesthetic sensibility has been at work. Quite simply, I do not immediately recognize the sentence as one that I would write.

This, in turn, reminds me just how personal the act of writing is. At its best, when one really writes and goes looking for a language beyond clichés and conventions, it appears that the results are as personal as a fingerprint. One writes by the rhythms of one’s heartbeat. Perhaps this is not literally so, but it is a pleasing metaphor, because something so intimate is at work, something so inalienably and naturally mine, that I cannot help but search for it in my physiology.

I do not envy my editor, trying to order, clean up the whispers of my blood.

Sneak Peaks

October 12, 2012

This is a time of writing catalogue blurbs, and giving the new book a face (well, and a backside, too, I suppose). And here it is, the first of The Crooked Maid‘s covers: the Bloomsbury US edition. Don’t she look gorgeous…?

Nova Scotia Mon Amour

Still flushed with the excitement of the WOTS Halifax festival. It reminds me how important it is to meet one’s readers face to face; to talk to colleagues; to step into a community of Canadian writing and reading. I had a blast. I got to gossip with Marina Endicott and to hear Donna Morrissey swear like a trooper on the Tall Ship Silva; chatted with Gary Blackwood and Scott Fotheringham; had sushi with Lauren Davis; heard Jim Williams read; and stood in David Adams Richards’ way.

As for my reading in Tatamagouche: the town continues to be a magic kingdom by the sea; Hanna and Chuck the most gracious, generous hosts; and Fables Club one of the most interesting and invigorating places to read. In other news: Maggie no longer (wo)mans the bar at Fables but runs her own restaurant, the Green Grass Running Water Cafe. Suffice it to say that her fishcakes are as masterly as her Long Island Ice Tea…

Word on the Street

Sept 16, 2012

Only one week to go, and I will be in Halifax, reading at WOTS 2012. It’ll be grand to be back in the Maritimes, see friends, revisit my favourite haunts. And (if I say so myself), it’s a kick-ass line-up: http://www.thewordonthestreet.ca/wots/halifax/authors/all And for those of youwho can’t get enough of their literature, or just want to indulge in the best margaritas north of Mexico, why don’t you come up to Fables in Tatamagouche on Friday night (the 21st), and join me for another little reading. I might even try some new material on the unsuspecting audience. Because (and this is strictly hush-hush), my new book is (almost, very nearly, but yes yes yes, as Molly Bloom would have it) finished… Hope to see you there!

Correction, with apologies

July 2, 2012

And just as I have cast aspersions on the profession of the critic, this fine review reaches me, via my publisher: http://www.weeklystandard.com/articles/viennese-waltz_645160.html

“In two books, [Dan Vyleta] has shown that he can take milieux far removed from us—thrilling ones, horrifying

ones—and use them, with care and decency, to examine the limits of just what a human being can bear.”

We are easy to get along with, us writers. Just praise us to high heaven, that’s all… Merci!

Balzac, quotable

June 27, 2012

“[Prostitutes] are like the literary critic of today, who may be compared with them in more than one respect and who attains to a profound unconcern with artistic standards: he has read so many books, forgotten so many, is so accustomed to written pages, has watched so many plots unfold, witnessed so many dramatic climaxes, he has produced so many articles without saying what he really thought, so often betraying art to serve his friendships and his enmities, that in the end he views everything with distaste and continues nevertheless to judge.”

This from a chapter entitled “What constitutes a whore” from Balzac’s The Harlot High and Low [trans. R. Heppenstall]. Not a good book, incidentally, in fact rather a bad one, which may explain the vitriol of this preemptive salvo. All the same, it made me laugh.

And now I will go back to reading David Bezmozgis, whom I am enjoying a good deal more, and who has had little need to bitch about his critics!

Guest-blogging Melodrama

June 7, 2012

I wanted to put this up months ago, but it somehow slipped through the cracks: a review (of sorts) of Stefan Zweig’s Beware of Pity that I wrote for Asymptote, a newish (and very stylish) literary magazine. http://asymptotejournal.com/article.php?cat=Criticism&id=31&curr_index=&curPage=search

BBC4’s A Good Read

March 25, 2012

A few weeks’ back Harriett Gilbert made my day by selecting Pavel & I as her pick for Radio 4’s ‘A Good Read’. Within an hour my email inbox had filled with messages from friends all across the UK who had caught the program. That day, Pavel & I broke into the Amazon.uk Top 10… Which is to say, people still listen to the radio when it’s as intelligently presented and pleasant to listen to as Radio 4. Harriett is so generous in her praise, I felt almost embarrassed when I listened to the programme myself. If you are interested, I have uploaded a part of it onto YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TDVmrVlCUzo&feature=youtu.be

Guest Reading

March 23, 2012

Can it really be that it is the end of March already? And that I have not written a blog entry in all this time? I did manage to guest-blog recently for Writers Read… Check out http://whatarewritersreading.blogspot.com/2012/02/dan-vyleta.html and http://americareads.blogspot.com/2012/02/what-is-dan-vyleta-reading.html

Saga

January 28, 2012

I am reading a collection of Icelandic sagas at the moment, on the recommendation of my friend, the Edmonton poet J. Mark Smith (get a hold of his collection Notes for a Rescue Narrative – it’s spectacular). Mark had mentioned to me the hypnotic quality of these sagas. Indeed, their flat, declarative prose manages to provide an oddly moving transcription of the brutality and beauty of Viking life. For someone like myself, who has a special place in his heart for the melodramatic excesses of a Dickens, Balzac and Dostoevsky, the sagas make fascinating, often disconcerting, reading. What touches me most, perhaps, is this: when emotion is allowed to break to the surface, as it does only intermittently, it does so in verse. “Recite this to the king,” says (grim) Skallagrim who has just killed a score of the king’s friends, along with two children who were in the king’s charge: “Halvard’s corpse flew/in pieces into the sea,/the grey eagle tears/at Travel-quick’s wounds.” [trans. B. Scudder].

Shit, man; Vikings!

Droodists of the world, unite

January 15, 2012

I read The Mystery of Edwin Drood – Dickens’s last, unfinished novel – over the holidays and find myself well on the way to becoming a Droodist, i.e. one of that sizeable group of Dickens enthusiasts / nutters who become obsessed with the book’s possible endings. I catch myself following odd lines of reasoning. For instance: all signs point to Jack Jasper, the villainous choirmaster, being the murderer; hence, he cannot be the murderer (if a murder did indeed take place). Who the hell is Dick Datchery, that “single duffer of independent means” who morphs into something very much like a detective by the end of the novel, and why is such emphasis placed on his resistance to wearing his hat? And how about that charming Mr. Tartar who shows up at a convenient moment and manages to turn Rosa “Pussy” Bud’s head? On the surface, he seems friendly, gallant and fundamentally harmless. Indeed he is conspicuously tidy, which, in a Victorian scheme of things, should guarantee his wholesomeness. The problem is this: the happy ending we are being prepared for, by the rules of Dickensian narrative, sees Rosa marry Neville Landless, her best friend’s brother. Tartar, then, is in the way. Does this mean he is a villain in disguise?

The real marvel, of course, is that 150 years or so after the fact, I (and a great many others) should become so absorbed in the mystery, and indeed that we should bother to read an unfinished novel at all. It says something, I think, about Dickens specifically and about the power of narrative more generally. Reading stories is one of those quintessentially human activities. We are built for narrative and crave for comprehension in the guise of plot.

Other books that have given me pleasure this winter: Manuel Rivas’s Books Burn Badly; Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life and Others; Marina Endicott’s The Little Shadows; Stefan Zweig, Beware of Pity. It’s been a good season for reading.

Cover Preview

28 Nov 2011

The US, UK and Canadian paperback covers of The Quiet Twin:

Writers’ Trust

October 27, 2011

The past two days my fellow WT nominees and I read together, first in Toronto, then in Hamilton. One might imagine a competitive spirit taking hold of us, but it was conspicously absent. Rather a relaxed, appreciative atmosphere prevailed; the writer’s joy of meeting good books. I found it a real pleasure to listen to the others read and to learn their rhythms, the way they vocalise their sentences (everybody reads according to some inner pulse). “Writers are good people,” Hal Wake, who organises the Vancouver International Writers Festival told me a week or two back (though he added a cautious, “for the most part” — I guess he has seen a few things in the course of his career). Judging by the past two nights – and the two weeks of Festivals I have just completed – he’s got it about right. Readers seem to be a very decent bunch also: what great audiences we had, stepping into each book with grace and eagerness, helping us out up there on the podium. Thanks, everyone, for coming out, for loving books and reading them with such passion, for the kind words exchanged before and after. I had a blast!

IFOA

October 24, 2011

The International Festival of Authors in Toronto is in full swing, and I am here enjoying one of those rare rockstar moments of being a writer: going to signings, readings, panels, hob-knobbing with the great and the good, hopping up to the penthouse “hospitality suite” to take advantage of the array of whiskey placed there for the writers’ pleasure (Q: Would there be more or less booze if we were painters, or composers?), having more or less coherent conversations about books. The writers here seem to have a shared sense of giddyness brought on by the knowledge that what we do, day in day out, is singularly innocent of glamour, which is to say we sit in cafes and basement offices, in public libraries and cluttered studies, tapping away at the computer, the patient, steady yoking of words to our purpose, usually with nothing stronger to hand than a cup of tea. The real rockstars, meanwhile, sit in bathtubs full of controlled substances blowing smoke at the crater that used to house the smoke detector (or so I like to believe). Ah well, I should have learned chords, not spelling, but then again, I am content with my three minutes of glamour, and growing impatient, too, to return to the solitude of my craft.

The International Festival of Authors in Toronto is in full swing, and I am here enjoying one of those rare rockstar moments of being a writer: going to signings, readings, panels, hob-knobbing with the great and the good, hopping up to the penthouse “hospitality suite” to take advantage of the array of whiskey placed there for the writers’ pleasure (Q: Would there be more or less booze if we were painters, or composers?), having more or less coherent conversations about books. The writers here seem to have a shared sense of giddyness brought on by the knowledge that what we do, day in day out, is singularly innocent of glamour, which is to say we sit in cafes and basement offices, in public libraries and cluttered studies, tapping away at the computer, the patient, steady yoking of words to our purpose, usually with nothing stronger to hand than a cup of tea. The real rockstars, meanwhile, sit in bathtubs full of controlled substances blowing smoke at the crater that used to house the smoke detector (or so I like to believe). Ah well, I should have learned chords, not spelling, but then again, I am content with my three minutes of glamour, and growing impatient, too, to return to the solitude of my craft.

US Cover

October 18, 2011

Hot off the designer’s table: the US cover for the paperback edition of Pavel & I, forthcoming in March. I must say, I love the monkey….

Hot off the designer’s table: the US cover for the paperback edition of Pavel & I, forthcoming in March. I must say, I love the monkey….

Coming soon: the US cover of The Quiet Twin!

Sasquatch Sighting

October 17, 2011

I am writing this sitting in my guest room at the Banff Centre which is just as about fabulous as everyone had told me it would be. http://www.banffcentre.ca/ It is the tail end of WordFest, when writers are invited to stay on at Banff to recuperate/discuss their craft/drink in the scenery for a few days. The festival itself was one of those quintessentially life-affirming affairs, was busy, buzzy, readers and writers talking books from morning till night. Landing in Calgary, the city sparkling in the clear, hard light of the prairies, the mountains on the horizon, I tried to reconstruct what my first glimpse of the city might I have been. I placed it at last in a comic book from the late 1970s or early 1980s in which a Canadian superhero team tries to capture Wolverine, that renegade Canuck. I remember some fisticuffs in the shadow of the Calgary tower and then later (in what may be a separate episode) some sort of shenanigans in the mountains of Banff. The names of the costumed heroes who make up the team escape me other than “Sasquatch” whose shaggy enormity must have impressed me as a child. It is hard now even to guess what reactions these characters and settings drew from the Czech-German boy that was I; most likely the one appeared as exotic as the other – the stuff of dreams – hence magical, and cool. I have yet to sight a Sasquatch (I did see a deer, and had a close encounter with a mountain raven, and the odd squirrel), but walking through the woods today, in the shadow of Sulphur Mountain, clapping my hands to attract the attention of bears (the theory goes that they choose to avoid humans; the thought occurred to me, halfway through my lonely walk, that if I did encounter a bear, I might not be given the opportunity to disprove the theory through my own testimony), I did keep my eyes peeled for anything large, shaggy and white. One lives in hope of magic.

I am writing this sitting in my guest room at the Banff Centre which is just as about fabulous as everyone had told me it would be. http://www.banffcentre.ca/ It is the tail end of WordFest, when writers are invited to stay on at Banff to recuperate/discuss their craft/drink in the scenery for a few days. The festival itself was one of those quintessentially life-affirming affairs, was busy, buzzy, readers and writers talking books from morning till night. Landing in Calgary, the city sparkling in the clear, hard light of the prairies, the mountains on the horizon, I tried to reconstruct what my first glimpse of the city might I have been. I placed it at last in a comic book from the late 1970s or early 1980s in which a Canadian superhero team tries to capture Wolverine, that renegade Canuck. I remember some fisticuffs in the shadow of the Calgary tower and then later (in what may be a separate episode) some sort of shenanigans in the mountains of Banff. The names of the costumed heroes who make up the team escape me other than “Sasquatch” whose shaggy enormity must have impressed me as a child. It is hard now even to guess what reactions these characters and settings drew from the Czech-German boy that was I; most likely the one appeared as exotic as the other – the stuff of dreams – hence magical, and cool. I have yet to sight a Sasquatch (I did see a deer, and had a close encounter with a mountain raven, and the odd squirrel), but walking through the woods today, in the shadow of Sulphur Mountain, clapping my hands to attract the attention of bears (the theory goes that they choose to avoid humans; the thought occurred to me, halfway through my lonely walk, that if I did encounter a bear, I might not be given the opportunity to disprove the theory through my own testimony), I did keep my eyes peeled for anything large, shaggy and white. One lives in hope of magic.

Memories of the Future

October 8, 2011

I picked up Memories of the Future by Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky (now there’s a name to drive any marketing department around the bend: “Can’t we just call him Kurt Sigmund or something?”) the other day: saw it, took it off the shelf, started reading the first page, and had that I’ve-just-stepped-off-the-cliff-into-the-unknown feeling that walked/floated me right over to the check-out. It felt like I was re-discovering Borges, or Kafka. The translator, I should add, from respect for her art, is Joanne Turnbull. She and Sigizmund kept me up till late last night…

In other news: the leaves on the sugar maples are turning Canada-red, the Jets are playing their first game since 1996 tomorrow (Guy Maddin must think he’s died and gone to heaven!), I am off to WordFest on Calgary on Friday.

In Season

October 6, 2011

Is it undignified to be childishly excited about the fact that the hockey season starts today? I say “childish” for a reason: one of my definitive memories from childhood is watching the Czechs play the Soviets on a too-small TV. Hockey wasn’t very popular in Germany then, but they would show the international tournaments, which are played in the late spring or early summer. I can still hear my dad hollering at the screen, sun streaming through the curtains. Czechs vs Soviets, a miniature 1968 on ice (without the tanks that is). I wish my dad was here tonight, to do some hollering with me.

Shortlist

September 28, 2011

My editor at Harper Collins called this morning with the news that TWIN has been shortlisted for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize. It’s been a busy day since then, one of those days when you learn to appreciate the phrase “my phone’s been ringing of the hook” (no hooks these days, but it has been doing that frantic, jerky ringing that’shalf siren call, half fire alarm). Thank you everyone for your support, you’re awesome! PS: And here is the CBC’s take on The Quiet Twin. Wow, mom, I’m on telly! http://www.cbc.ca/books/2011/09/fall-fiction-prizes.html

More Life and Fate

September 20, 2011

Readers of this blog know how much I admire Vasily Grossman’s great novel of the Soviet Union in the year of the Battle of Stalingrad. Here is an interesting piece by his English translator, Robert Chandler, whose contribution is in danger of being ignored even as the BBC is launching a dramatization of the book: http://www.newstatesman.com/blogs/cultural-capital/2011/09/translation-translator-life

Eden Mills Festival

September 19, 2010

This will be brief and to the point: the Eden Mills Festival rocks. Great atmosphere, great line-up, lovely organisers. And what a place – an entire village that literarally threw open its doors to a horde of writers. And served them home-baked pie. ‘Good goddam pie’, as Agent Cooper used to say on Twin Peaks. Just a fantastic day. Highlights included: watching Jill Murray peel herself out of a polyester-padded Batman suit (one shoe got stuck); listening to Robert J. Wiersema’s rendering of his teenage discovery of Bruce Springstein through the miracle of MTV (I was sure he was going to launch into an air guitar solo right there behind the reading lectern); sitting in a crowded chapel, listening to some of Canada’s best poets read, about English-teaching speed skaters in skin-tight suits (Prsicila Uppal), identities lost and found amongst the street corners of Havana (Dionne Brand), and about Saskatchewan bugs and their soil-churning heroics (Lorna Crozier); watching the smokers bum cigarettes as the supply slowly dried up in the course of the day (no cigarette machines in Eden Mills; I think Nino Ricci was the final port of call). That and the crowds: the streets were full of book-lovers, old and young; teenage Goths and veteran readers, beer guzzlers and prim old ladies, and a whole congregation of eager kids, all there to celebrate stories and the rhythm of words. It did not hurt, of course, that we had beautiful September sun. And pie.

Fall

September 15, 2010.

He

Who has no house now,will not build one any more

Who is alone, will remain so for the longest time

Will stay up, will read, and write long letters

Will walk unsettled up and down in streets, while the leaves are blowing

‘Fall Day’, Rainer Maria Rilke

This has been a summer of grief for me. My father died a month ago. I do not wish to write about this, or at any rate not yet. But it is Fall now, and my blog has lain abandoned; the Festival Season is upon us, I am coming out of my shell to read and to talk about writing. I will do so with sadness, but gladly, too, because it is a fine thing to share one’s work with other people and create a moment of connection, through something as intimate as a book.

Sitting in Judgement

June 10, 2011

I finished my reading tour, recuperated in Prague (though my liver might argue for another sort of verb…), and am now back in the saddle. The tour was fun: always nice to meet people who run their own independent bookstore on the strength of their wit and the familial relationship to their customers, as in the case of Vienna’s Erlkönig. And the Tübingen Book Festival turned out to be the sort of event that takes over a whole city: readings at every corner, a holiday atmosphere throughout its busy streets. I read in the room otherwise reserved for criminal trials in the Tübingen court house; they put me on the judge’s seat. No mallet, as it turns out, the modern world has swapped it for a buzzer, but it was fun declaiming from up high, with a radio journalist sitting where the defendant would usually take his or her place, and stretched a microphone towards me. Hilary Mantel’s A Place of Greater Safety kept me company throughout my trip: the French Revolution, refracted through a great literary imagination. I am often hesitant about embracing the label “historical fiction” where my own work is concerned: it seems to carry too many assumptions about its aesthetics and aims. But if Mantel’s book is historical fiction, I should lose my ambivalence about the tag.

Climbing the past

May 26, 2011  On a long walk through Vienna today, I found that the city authorities have put a climbing wall into the flank of one of the monumental anti-aircraft towers that were built under the Nazis and continue to litter the city (my understanding is that they are very difficult to remove: their walls are too thick). It is tempting to see in the slow, laborious if joyful ascent of the climbers a deliberate symbol for the country’s attempts (hesitant as they sometimes have been) to come to terms with the past and scale its challenge – a symbol that acknowledges that one will have to make the climb time and again; that every climber must start at the bottom and find his or her own way up. It also, it must be say, looks very cool, rising out of a playground just a few blocks from the Naschmarkt.

On a long walk through Vienna today, I found that the city authorities have put a climbing wall into the flank of one of the monumental anti-aircraft towers that were built under the Nazis and continue to litter the city (my understanding is that they are very difficult to remove: their walls are too thick). It is tempting to see in the slow, laborious if joyful ascent of the climbers a deliberate symbol for the country’s attempts (hesitant as they sometimes have been) to come to terms with the past and scale its challenge – a symbol that acknowledges that one will have to make the climb time and again; that every climber must start at the bottom and find his or her own way up. It also, it must be say, looks very cool, rising out of a playground just a few blocks from the Naschmarkt.

News from the Front

May 26, 2011  I had my first Vienna reading last night, after a lovely night in Cologne at Jens Bartsch’s cozy independent bookstore (Buchhandlung Goltsteinstrasse – worth a trip!). Last night’s reading was in Thalia on Mariahilfestrasse, one of Vienna’s busiest shopping streets. I got a little nervous there: it’s odd, after all, reading out my Viennese story in my (northern) German accent (I was reading from the German translation) to an audience of Viennese, many of them born and bred. My listeners were gracious though, and seemed to enjoy the chance to discover their city anew, instantly familiar and yet made fresh by the idiosyncrasies of my phrasing and the discrepancy of accent. I might have stumbled on a new version of the Brechtian alienation effect there… They have put me up, incidentally, in a fabulous little hotel in the 7th district, which features a sort of white leather update on the Freudian couch (see pic). The ceilings are so high I cannot make out the stucco without wearing my glasses… and there’s an Illy espresso machine en-suite. This is as rockstar as it gets for a writer; I must say I am enjoying it!

I had my first Vienna reading last night, after a lovely night in Cologne at Jens Bartsch’s cozy independent bookstore (Buchhandlung Goltsteinstrasse – worth a trip!). Last night’s reading was in Thalia on Mariahilfestrasse, one of Vienna’s busiest shopping streets. I got a little nervous there: it’s odd, after all, reading out my Viennese story in my (northern) German accent (I was reading from the German translation) to an audience of Viennese, many of them born and bred. My listeners were gracious though, and seemed to enjoy the chance to discover their city anew, instantly familiar and yet made fresh by the idiosyncrasies of my phrasing and the discrepancy of accent. I might have stumbled on a new version of the Brechtian alienation effect there… They have put me up, incidentally, in a fabulous little hotel in the 7th district, which features a sort of white leather update on the Freudian couch (see pic). The ceilings are so high I cannot make out the stucco without wearing my glasses… and there’s an Illy espresso machine en-suite. This is as rockstar as it gets for a writer; I must say I am enjoying it!

Swiss Review

May 4, 2011 The German language reviews are trickling in. Today this reaches me from Switzerland, a review in annabelle magazine. In brief, for those who do not read German, the review says that the book is awesome… 😉 http://www.annabelle.ch/kultur/bucher/dan-vyleta-bose-marchen-16131

Italian Q&A

April 27, 2011 Liberi di Scivere did a recent interview about the Italian edition of Pavel & I, L’uomo di Berlino. An English version is available, though I like the ring of the Italian. “Ho difficoltà a scendere dal letto il giorno dopo.” Indeed. http://liberidiscrivere.splinder.com/post/24491216/intervista-con-dan-vyleta

Q&A

April 12, 2011 Here is a recent interview with Hubert O’Hearn from the Thunder Bay Chronicle-Journal. Good final question.

Reading Journey

25. March 2011  I am making arrangements for a little reading tour through Germany and Austria this May. The German phrase is “Lesereise” – “reading journey”; it de-emphasises the promotional dimension of the trip, and imbues it instead with the possibility of discovery. I am hoping that it will be a journey in this latter sense; that the readings, the questions, answers, the nights spent in hotels, will add up to something that feeds the soul. It is also a chance for me to discover the German text anew, and to test its rhythms: what I typically do, is read a short passage in English (hoping that my audience will pick out the gist, and grow familiar with the sound of my prose), then re-read the same section in German. The real challenge, of course, will be reading in Vienna. My German is a far cry from the musical Viennese, and I am hoping the audience will accept its rhythms. The thing is: returning to Vienna, I feel like I am going home. Reading Dates: Koeln – 24.5. Buchhandlung Goltsteinstraße Wien – 25. 5. Thalia Mariahilferstraße Wien – 26.5. Buchhandlung Erlkönig Muenchen – 27.5. Tschechisches Zentrum http://www.tuebinger-buecherfest.de/start.html Tuebingen – 28.5. Tübinger Bücherfest

I am making arrangements for a little reading tour through Germany and Austria this May. The German phrase is “Lesereise” – “reading journey”; it de-emphasises the promotional dimension of the trip, and imbues it instead with the possibility of discovery. I am hoping that it will be a journey in this latter sense; that the readings, the questions, answers, the nights spent in hotels, will add up to something that feeds the soul. It is also a chance for me to discover the German text anew, and to test its rhythms: what I typically do, is read a short passage in English (hoping that my audience will pick out the gist, and grow familiar with the sound of my prose), then re-read the same section in German. The real challenge, of course, will be reading in Vienna. My German is a far cry from the musical Viennese, and I am hoping the audience will accept its rhythms. The thing is: returning to Vienna, I feel like I am going home. Reading Dates: Koeln – 24.5. Buchhandlung Goltsteinstraße Wien – 25. 5. Thalia Mariahilferstraße Wien – 26.5. Buchhandlung Erlkönig Muenchen – 27.5. Tschechisches Zentrum http://www.tuebinger-buecherfest.de/start.html Tuebingen – 28.5. Tübinger Bücherfest

Eating Chinese bitterness

March 19, 2011

I read a newspaper piece some weeks ago that described the practice, apparently common now in Chinese job ads, to ask for workers willing to “eat bitterness”. The phrase has stayed with me ever since. It is at once very alien (for is it not a taboo in our culture for the employer to admit that the job they offer is, at bottom, undesirable? – imagine Walmart telling its cashiers to get ready to eat bitterness) and at the same time deeply familiar (for have we not all been called upon to eat bitterness from time to time? And how many men and women have to stand in line somewhere, every day, to partake in the privilege of eating their corner of bitterness?). It is a poetic phrase, in that it is precise and evokes an image that is immediately understood long before it is decoded. I hope it takes root in English; it is important, this poetry of the every day.

Twenty Thousand Streets

Twenty Thousand Streets

March 1, 2011 I am reading Patrick Hamilton’s Twenty Thousand Streets under the Sky from 1935 at the moment. It’s the third Hamilton novel I have picked up, and they all have been good; he reads like an elder cousin of Graham Greene’s and conjures a Britain that is all but gone. It is good to see his books re-issued (I am reading the NYRB edition). Like many other writers I have spoken to, I hold the superstitious belief that a book finds you when you need it. I have, of course, no idea what I need Hamilton for, but that is of no consequence.

Guardian Hitlist

Feb 16, 2010 The Guardian published my Top 10 Great Books written by writers who (like myself) came to their language of expression late in life. http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2011/feb/16/dan-vyleta-top-10-books-second-languages Below, is a full version of my essay of how I came to write in English.

Not My Mother’s Tongue

Not every journalist will broach it. Some are too polite, I suppose. Others suspect a trick of some sort, and refuse to play along. It will not have escaped them that I speak with an accent. As accents go, it is a hard one to place. Northern British vowels bump into soft German Vs; my O in “south” has acquired a touch of a Canadian vowel shift; and my wife insists that I have taken to saying “prawblem”, a sure sign of too much American TV. The thing is, I am susceptible to the speech patterns that surround me. Each leaves its mark. I learned my English in a German school. The first class, I remember, focused on greetings. There was a special hand motion to indicate the rise and fall of intonation. We were doing what language teachers call a “group drill”. “How Are You?” we sang in unison. “Fein Sank You.” We had yet to learn how to handle the “th”. To cut to the chase, though: what in the world possessed me to write in a language other than my mother tongue? Strictly speaking, that wasn’t German either. My family are Czech. Bohemians. From Prague. I learned Czech first, then switched, growing up, trying my best to blend in with the German world that surrounded me. Like many an immigrant child I wished above all to belong. It left my Czech stunted, a kitchen language used primarily for fielding my grandmother’s continuous demands that I should eat. Eat more, that is. I was raised on bread, butter and cold cuts. For health, you see. The Czech word for enough is dost. But I still owe you an answer. Why settle on a tongue that is not your own? To write novels, no less. Was it chutzpah, the need to brag? A belated “fuck you” to Herr Menzel who dared to give me a C? The answer is that English is my own, never mind when I acquired it. That I chose it the way one chooses a spouse, which is to say I fell in love with it, courted it, proposed, and was accepted. I wrote my first cheque in English; met my life’s companion in English. I can no longer remember a day when I did not think, and dream, in English. There was never a question in my mind that I would write my books in anything else. Which is not to say that it doesn’t make a difference that I grew up on the rhythms of two other tongues. There used to be, in antisemitic pamphlets of the nineteenth century, the claim that Jews had no organic connection to the language of their “host” nations and hence were unable to produce genuine literature. It was a charge levelled at Heinrich Heine, for instance, the author of some of Germany’s most enduring poetry. A variation of the claim sometimes hovers over discussions of writing by those who, like me, were not born with their language of expression (the technical term is “exophones”; once you start digging you will find we are a dime a dozen, a whole legion of upstarts taking over your tongue!). It is true that for many of us our relationship to our adopted language is not territorial. Mine is an English that I cobbled together from the many places I have lived and the books I have read, a transnational quilt. It limits me in some respects, and opens avenues. The Quiet Twin is set in the Austria of 1939, amongst speakers of Viennese German. My (northern, “Prussian”) German would struggle to capture the time and place. I have spent years in Vienna, and am familiar with its patter; I may be able to imitate it, but it does not belong to me. In English, by contrast, I was free to create a language precisely suited to its purpose, neither British nor Canadian, inflected with the rhythms of German grammar and that joy of expression peculiar those reluctant Habsburg sisters, Austria and Czechoslovakia. In English, then, it came alive, this city of a bygone era, spontaneously and without effort, spilling out with every chapter that I wrote. As a writer, one cannot receive a greater gift than that.

Toronto Star Interview

Feb 13, 2010 Here is an interview with Vit Wagner from the Toronto Star. We met in Toronto last week and compared notes on growing up as children of Czech émigrés… Note my attempt to look fierce for the photo (see Feb 4 blog entry). http://www.thestar.com/article/937514–the-neighbours-are-watching

Go ahead and judge it by its cover

Feb 11, 2011

[Note: I wrote this little piece about The Quiet Twin‘s cover for The Savvy Reader Blog: http://thesavvyreader.ca/2011/go-ahead-and-judge-it-by-its-cover-by-dan-vyleta/ ] For the most part, novelists do not choose their covers. Günter Grass does, but then again, he designs the cover-art himself and has a Nobel prize for literature sitting on his shelf, so he may not quite count. The feeling is, no doubt rightly, that writers should spend their time writing and leave it to the professionals to choose an image that will serve as the public face of their work. When I send in a manuscript, I am politely asked for my ideas; some months later I receive the first version of a possible cover. If I hate it, the artist goes back to the drawing board. And so a dialogue ensues that in the end produces what will end up on the shelf of your local store. It is an odd business this, waiting for one’s publisher’s art department to dream up the physical incarnation of your novels. After all, it is yours in a way few things in life are: novel-writing is a solitary, intimate art, and in quite a few writers, yours truly included, this intimacy creates an attachment that is resistant to outside intervention. We don’t like others to meddle with our words and be it only to provide them with a protective sleeve. All the same, the cover matters: not just because it represents the novel to its prospective readers; but also because in my own mind cover and book will soon become fused. The novel transforms from a string of sentences into an object whose shape has been determined by someone else. Writers are aesthetes. We want our children to be beautiful. When my editor for The Quiet Twin first raised the question of a cover, therefore, I found myself casting around for pictures to share with the artists involved in its design. It was less the hope of providing a concrete image that prompted my search, than the hope that I would be able to communicate something about the emotional flavour of the book I had written. Almost at once I found myself drawn to a collection of police photographs dating from between the turn of the last century to the mid 1950s which were shut away in a box at the back of my closet. These pictures were amassed during a period of my life when – as a research student in history – I was hunting down all things connected to criminal activity in Vienna prior to the advent of colour photography. I own boxes and boxes of photos and photocopies, along with shelf-fulls of specialist literature, that I take care to hide from view when my landlord visits, who might not care for my mug shots of murderers, nor for the black and white photos of their victims, crumpled on apartment floors, or laid out on coroners’ slabs. Nobody wants a whack-job for a tenant; it might be a struggle to convince him I am merely a writer. Back then I was working on a book that sought to analyse the stories about crimes and criminals that the Viennese told one another a hundred or so years ago. I found the pictures in court files and newspapers, in libraries and archives, and swallowed more than my share of century-old dust. When I dug them up again some months ago to look for ideas for a book cover, I recognized each of them at once and was amazed, in fact, at how accurately I recalled them. Clearly, these snapshots of crime and death had left their mark on me and become part of my pictorial vocabulary. It is not easy to give the reader a sense of the pictures. It would be wrong to describe them as murky. The corpses and crime scenes depicted in them have crisp, hard edges. One can have no doubt as to the reality of the things that one sees. But within this crispness there sits a patchwork of shadows that seem as though stitched on. One wants to pick at them with a fingernail and peel them off; see what lies hidden underneath. There is a voyeuristic quality to many of the pictures. Often the photographer seems to be standing in the doorway, on the threshold of things. One sees what one is not meant to see. Not one of the victims had time to clean up their bedrooms before the police came knocking. Not all these pictures are gruesome. Some show spaces rather than people: the street corner where a robbery took place; the sparsely furnished living room of a murdered prostitute whose washing still hangs from a line; the inner courtyard of a tenement block where a man had thrown his wife out of the window of their third-floor bedroom. This last picture would not let me go: I recognized it as the courtyard in which my story was taking place; recognized the shape and arrangement of its many windows and the plain, dirt-smeared walls. In Vienna, many houses, including some of the council-built tenement blocks for workers, have elaborate facades overloaded with ornamentation, resulting in a meringue of mouldings and statues, of mosaics and reliefs. It is in the buildings’ courtyards that plainer, dirtier walls predominate, strewn with little windows behind which are lived the private lives of ordinary Viennese: in close proximity to one another, and within a context of social diversity ensured by the architecture itself – for the rooms located in the rear and side wings of such buildings do not have any windows out onto the street and consequently command much lower rents than the grandly bourgeois apartments at the front. What the picture in question shows is the squalid facade of such a Hinterhaus. One Therese Bittermann lived here in May 1937 with her husband, Franz, and his mother. Franz had read a story in the papers of a man ridding himself of his spouse by pushing her out the window. The idea stuck. Nobody saw him do it, but many heard Therese’s scream. When Franz approached her broken body in the courtyard he did so without betraying any emotion. All he said was: “She’s already dead.” Franz Bittermann was sentenced to death but the sentence was commuted. In 1943, when the Nazi government transferred him from prison into the Mauthausen concentration camp, he fulfilled the intentions of the original verdict by hanging himself by the neck. There is a picture of Franz looking out of the window shoulder-to-shoulder with the investigative judge: he is pointing down into the yard and explaining his deed. He has thick brown hair that he wears combed back from his forehead; a handsome man in a dark suit. I have no image of his wife. There were three other pictures that caught my attention. The corpse of an old crone, lying prone on her back, her throat slit underneath a bloom of flowers that make up the pattern of her oppressive wallpaper. The image of a big marital bed, its silk sheets soaked with blood. And, worst yet, the naked body of a woman floating face-down in the murky water of her bathtub. Her leg has been cut, at the knee, so it bends back at an acute angle. Her skin is pale and slick. Only one buttock breaks the surface of the water. I sent all four of these images, myself not quite knowing why, but sensing dimly that, between them, they evoked a claustrophobic sense of threat that I also found within the pages of the novel. My editor wrote back to say that these pictures were “interesting”. Two months passed and I received the cover. Therese and Franz Bittermann’s backyard had been re-arranged for it, the photographic angle had been changed. For all that, I knew at once where I was, and knew, too, that this one was right for the nov

el. Everybody who had read the book agreed. We never considered asking the artist for another cover concept. I did not choose the cover of The Quiet Twin, but I instantly recognized it as belonging to my book.

German cover and blurb

February 5, 2011 I just received this very nice catalogue page about the German edition of The Quiet Twin.

Looking mean for the camera

Feb 4, 2011

A long day of meetings and interviews in Toronto today. Everybody is excited that the book is finally out (myself most of all!). I had to pose for a few photos, too, which is always a little awkward, unless you are Naomi or Claudia, I suppose. The photographer for the Toronto Star, Rick Eglinton, insisted I did not look “mean” enough. We worked on some good old frowns; made sure I pushed my woolly hat low into my brow. Serious book, serious author. When my mom sees the picture she will say: “Why aren’t you smiling, you always look so gloomy”. It is hard to please both the critics and one’s mother.

E-vite – Guelph reading on the 7th of Jan

Viennese Love Letter (featured in The Afterword)

January 26, 2011

I am guest editing The National Post’s book blog, The Afterword, this week. To read ‘Viennese Love Letter’, please click: HERE

I am guest editing The National Post’s book blog, The Afterword, this week. To read ‘Viennese Love Letter’, please click: HERE

From Vidocq to CSI: Milestones in the History of Criminology and Forensic Technology (featured in The Afterword)

January 25, 2011 I am guest editing The National Post’s book blog, The Afterword, this week. To read ‘From Vidocq to CSI’, please click: http://arts.nationalpost.com/2011/01/25/dan-vyleta-from-vidocq-to-csi-milestones-in-the-history-of-criminology-and-forensic-technology/

Birth of Twin (featured in The Afterword)

January 24, 2011 I am guest editing The National Post’s book blog, The Afterword, this week. To read ‘Birth of Twin’, please click: http://arts.nationalpost.com/2011/01/24/dan-vyleta-birth-of-twin/

First Review of Twin

Jan 20, 2011 The first of the reviews has come in and brings up the age-old question: if a book has a murder in it, is it crime fiction? Personally, I don’t care: a book is a book. It either is interesting, or it is not. I am happy, in any case, that The Quiet Twin has been judged the former… For the review, see: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/arts/books/new-in-crime-fiction-a-guide-to-the-latest-mysteries-and-thrillers/article1876109/

Full Paper Jacket

4 January 2011

Last Year’s Books

1 January 2011 2010 was another year of reading fat books. I am not entirely sure why I gravitate to books the size and heft of bricks. I suppose the length allows certain things to take place that shorter books struggle to replicate: we spend more time inhabiting that world whose call we have answered, and invest more of ourselves in it. As a boy, I – much like Bastian Balthasar Bux, the hero of Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story – dreamed about a book that would never run out of pages. It is a fine thing to discover the inner child in me, now that what is left of my hair is turning gray beyond denial. Of the various fat books I read, a few stand out in particular: Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo with its batshit plot and French colonial overtones; Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy whose breadth of invention left me speechless and which filled my head with dreams of the Red Planet; Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove with its patient, level-headed prose and its total commitment to its characters; Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend in which the ageing writer seems unwilling, at times, to hide his anger behind his usual veil of humour. I also read a slew of Ross MacDonald’s Lew Archer novels, literally reading one after the other, in the intense heat of late summer. MacDonald, who was raised in Kitchener, Ontario, settled in California and spent a life-time observing it with the bemused intensity of the foreigner. Something about the form of the detective novel opened this world up to him and allowed him to describe it. I have not been this hooked on a cycle of crime novels for quite a few years. I also read some shorter fiction: a fantastic collection of German stories which a friend gave me, which included, amongst its obscure gems, Jacob Wassermann’s remarkable ‘Lukardis’; Isaac Babel’s wonderful ‘Odessa’ stories; a string of Alice Munro stories, including one, whose title now eludes me, in which a young girl watches her father share a drink with a mentally unstable and potentially violent neighbour, a story so densely atmospheric and suggestive that an Ontario school board felt the need to ban it from the classroom. As for my New Year’s Resolution, it coincides with the advice I sometimes give to students: Read Much. Read much, read eclectically, following threads so personal they resist the dictates of marketing and fashion, read daily, with pleasure, like a child, searching for stories and books that you hope will never end.

For Pet Lovers

November 19 2010 Gérard de Nerval, who owned a pet lobster and took it for walks around Paris, explained his devotion to crustaceans in the following terms: “Why should a lobster be any more ridiculous than a dog? …or a cat, or a gazelle, or a lion, or any other animal that one chooses to take for a walk? I have a liking for lobsters. They are peaceful, serious creatures. They know the secrets of the sea, they don’t bark, and they don’t gnaw upon one’s monadic privacy like dogs do.” (trans. Richard Holmes) I find it reassuring that a man can love lobsters in this manner, though it is also true that Nerval had several nervous breakdowns and feared he was insane. I am reading some of his short fiction at the moment, having spotted a collection of his work in the library. My cats, meanwhile, look on, and only intermittently deign to gnaw on my monadic privacy, such as it is.

Pattern Recognition

November 16, 2010

I have been reading lots of Dumas (père) recently, followed by William Gibson’s Pattern Recognition, which I picked up on a hunch and enjoyed tremendously. There is not much that would connect the nineteenth century master of swashbuckling adventure yarns to the visionary inventor of cyberpunk, other than a shared love for story, perhaps, and an obvious, heartfelt interest in their characters. Both qualities are notably absent in the kind of narcissistic, solipsistic writing that I keep stumbling over in a variety of contexts, and that its authors are keen to describe as a “sharing of themselves”, a phrase whose purported generosity often masks an act of self-important imposition. Writers, I feel, should take the trouble to interest themselves in lives other than their own. There we have it: an honest-to-God rant, posted on my blog, that theatre of self-publishing most responsible for narcissistic “sharing”. I should shut up now, and go do some writing.

Indian Flowers

November 13, 2010 My friend Gwyn is cycling the world. He is currently making his way along the western coast of India, heading south from Mumbai to God knows where. Today, on the road, he was followed around by a young man on a scooter. The young man pulled him over, and they waited until a group of further men caught up with them, who then proceeded to present Gwyn with a garland of flowers. I cannot think of a more lovely gesture of welcome made to a total stranger: unprompted, without calculation, the very opposite of the ritual smiles issued by minimum wage workers who greet us at the entrances to certain types of shop. It is a gesture so generous and simple that, in a great many contexts, it would arouse nothing other than suspicion, the vague feeling one was being set up for something. As for Gwyn, he cycles on: flower-clad, followed by children, by moped drivers, the well-wishes of strangers who show him the way. Follow Gwyn’s travels at: http://www.crazyguyonabike.com/doc/page/?o=RrzKj&page_id=171761&v=56

Czech Edition of Pavel

Oct 3, 2010

News arrived today that the Czech edition of Pavel & I – Pavel a ja – has been published. My contacts in Prague (and how smugly cold-war does that phrase sound?!) tell me it is yet to show up on the bookstore shelves, but this seems to be a matter of days. The cover, in any case, is super cool. I don’t have a copy yet, but once it gets here I will make sure to send it on to the wonderful Czech jazz composer who invited me to his home in Edmonton, and told me how much he had enjoyed the (English version) of the book and how closely it conformed to his memories of Berlin in the late 1940s.

News arrived today that the Czech edition of Pavel & I – Pavel a ja – has been published. My contacts in Prague (and how smugly cold-war does that phrase sound?!) tell me it is yet to show up on the bookstore shelves, but this seems to be a matter of days. The cover, in any case, is super cool. I don’t have a copy yet, but once it gets here I will make sure to send it on to the wonderful Czech jazz composer who invited me to his home in Edmonton, and told me how much he had enjoyed the (English version) of the book and how closely it conformed to his memories of Berlin in the late 1940s.

Galley Slave

Sept. 4, 2010.

I had a nice email this Friday from my Czech publisher, JOTA, asking for some lines outlining my connection to the “ancestral land”. Vanda (the foreign rights manager) had some lovely things to say about Pavel. I wrote back at once, albeit somewhat beer-fuelled, waxing lyrical about my grandmother (who was Czech, and formidable, and rotund, and kind). It don’t think it’s necessarily what they had in mind… Other than that I have been ploughing through the galleys of The Quiet Twin. It looks nice, cleaned-up and typeset, and contrary to my expectations I had fun, reading through the story one more time. This is it then, my final sweep through the manuscript. Always difficult to let go. Only I won’t, because right after I am done, there’s the German translation waiting for me. I like to read through the German version and discuss it with my translator and editor. Perhaps I shouldn’t; it’s a very difficult thing, judging your own prose as rendered in another language and through another person’s sense of style. All the same, it’s hard to stay on the sidelines when something as personal as your novel is at stake.

Matters of Taste

July 17 2010 I was reading Dead Souls and stumbled over this piece of Gogolian wit (and wisdom): “There’s no accounting for taste. Some like the priest, others like the priest’s wife…” I want a T-shirt with that slogan.

World Cup

June 28, 2010.

Watching the World Cup, with its various referee-induced injustices, I begin to wonder how much of its drama derives from these injustices. It’s a powerful emotion, helplessly watching your team being screwed out of their hopes by a bad call which, once made, cannot be unmade, no matter whether or not the referee has realised his mistake. When is the last time you have watched a play, or a movie, and felt what much of Mexico felt when Tavarez scored his offside goal… ? (ditto for the Lampert bounce, the two disallowed USA goals, etc). The other thing I find intriguing is how great a stake commentators seem to have in declaring that the better side won, irrespective of how the game unfolded. It seems that, retrospectively at least, justice must be declared to have prevailed. Thus every winner has deserved their win. It’s like a Sirk picture where, after all the upset and the mess, the final reel provides reconciliation (though here, subversively, it is the strife, the upset you remember, rather than the tagged on happy end).

“Anybody can write a short story – a bad one, I mean…”

June 14, 2010.

This from the preface to the ‘Biographical Edition’ of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island; it made me laugh, but he was on to something. At times a novel does seem just awfully long… “Sooner or later, somehow, anyhow, I was bound to write a novel. It seems vain to ask why. Men are born with various manias: from my earliest childhood it was mine to make a plaything of imaginary series of events; and as soon as I was able to write, I became a good friend to the papermakers. Reams upon reams must have gone to the making of Rathillet, the Pentland Rising, the King’s Pardon (otherwise Park Whitehead), Edward Darren, A Country Dance, and a Vendetta in the West; and it is consolatory to remember that these reams are now all ashes, and have been received again in the soil. […] Although I had attempted the thing with vigour not less than ten or twelve times, I had not yet written a novel. All – all my pretty ones – had gone for a little, and then stopped inexorably, like a school-boy’s watch. I might be compared to a cricketer of many years’ standing who should never have made a run. Anybody can write a short story – a bad one, I mean – who has industry and paper and time enough; but not every one may hope to write even a bad novel. It is the length that kills. The accepted novelist may take his novel up and put it down, spend days upon it in vain, and write not any more than he makes haste to blot. Not so the beginner. Human nature has certain rights; instinct – the instinct of self-preservation – forbids that any man (cheered and supported by the consciousness of no previous victory) should endure the miseries of unsuccessful literary toil beyond a period to be measured in weeks. There must be something for hope to feed upon. The beginner must have a slant of wind, a lucky vein must be running, he must be in the one of those hours when the words come and the phrases balance of themselves –- even to begin. And having begun, what a dread looking forward is that until the book shall be accomplished! For so long a time the slant is to continue unchanged, the vein to keep running; for so long a time you must hold command the same quality of style; for so long a time your puppets are to be always vital, always consistent, always vigorous. I remember I used to look, in those days, upon every three-volume novel with a sort of veneration, as a feat – not possibly of literature – but at least of physical and moral endurance and the courage of Ajax.”

Robert Louis Stevenson

Cover

May 28, 2010  The Quiet Twin has acquired a cover. It’s nice to learn what my novel looks like, part of its transition from the thing I dreamed up in my study, to the thing I want to share with my readers. With Pavel & I, I have gotten used to the various covers and the typeface it is printed in, and now associate both with the the novel; I remember, however, how disconcerted I was when I fist received the proofs and realised that the words looked different on the page. Well, here it is, my first sense of what the new book will look like when it lands on my shelf. I must say it looks mighty pretty.

The Quiet Twin has acquired a cover. It’s nice to learn what my novel looks like, part of its transition from the thing I dreamed up in my study, to the thing I want to share with my readers. With Pavel & I, I have gotten used to the various covers and the typeface it is printed in, and now associate both with the the novel; I remember, however, how disconcerted I was when I fist received the proofs and realised that the words looked different on the page. Well, here it is, my first sense of what the new book will look like when it lands on my shelf. I must say it looks mighty pretty.

Line edits

May 24, 2010. I’ve just spent a week going over the last set of line edits for THE QUIET TWIN. Line editing is a hard-fought contest between the drive to “clean up”, i.e. conventionalise the language, thus producing a manuscript that “flows” without resistance, versus the desire to preserve all that is creative, unique, demanding, and sometimes cumbersome about the style the book is written in. Unfortunately this forces one to read as no-one other than an editor or author should ever be reading a novel: rather than immersing oneself in the story, one tackles the book purely as a sequence of sentences. Needless to say, it nearly did me in. It is done though, and the book a little sharper, one step closer to being finished.

Exercising Freedom

May 14, 2010.

My German editor has kindly given me a copy of a short story collection by Hungarian writer Péter Nádas, recently published by Berlin Verlag (Freiheitsübungen und andere Kleine Prosa — Exercises in Freedom and other small prose). I don’t know whether it has been translated. It’s a slender volume of essays and stories and texts that are neither essays nor stories but some intriguing middle form. I read it on a train and found myself marking passages. Here’s one, about the killings of Nicolae Ceauşescu and his wife Elena on Christmas day, 1989. I remember the events vividly from my own youth; sat glued to a television, in some Austrian hotel, cheeks flushed from skiing. Nádas describes watching the documentary footage of the execution a near-decade after the fact. He writes: “These films have re-awakened fundemental moral and aesthetic questions in me for which I have not found an answer in the past ten years. Level-headedly, I observed myself enjoying the despot’s murder. I understood that I should feel ashamed for the pleasure I was taking, but all the same I did not feel ashamed. In me there was no mercy, and I did not find any pity for this married couple. I am a supporter of proper judicial procedure. Nonetheless, my conscience remained silent. I am not a supporter of the death penalty. Nonetheless, the brutality of the actions did not violate my good taste.” (my translation) Elsewhere, Nádas describes a character in the following terms: “His metabolism was such, he himself said, that he could survive on air (and a little beer). He was as thin as a thread. Due to his large head, however, it was impossible to thread him into anything.” You get a feeling Nádas is writing about himself.

Bagels

April 8, 2010

In Montreal, only my second visit to this wonderful city. Finally managed to sample both the smoked meat and the Montreal-style bagels both of which turn out to be fine things (for New Yorkers: here’s a place where you can sample these locally http://www.mileendbrooklyn.com/). Other than being a tourist, I am meeting a pair of very talented translators who have taken a shine to Pavel — there is some talk about a French translation… In the meantime, The Quiet Twin is working its way towards a cover: a strange thing, not knowing what one’s book looks like.

In Montreal, only my second visit to this wonderful city. Finally managed to sample both the smoked meat and the Montreal-style bagels both of which turn out to be fine things (for New Yorkers: here’s a place where you can sample these locally http://www.mileendbrooklyn.com/). Other than being a tourist, I am meeting a pair of very talented translators who have taken a shine to Pavel — there is some talk about a French translation… In the meantime, The Quiet Twin is working its way towards a cover: a strange thing, not knowing what one’s book looks like.

Dickensian Stock Exchange

March 28, 2010